Note: This is a summary of several posts I wrote in late 2007/early 2008

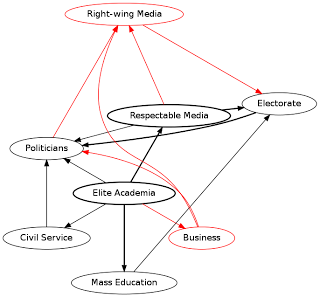

I was watching Channel 4 news, and what struck me for the first time was that Channel 4 appeared to have a more clearly defined and clearly expressed position on the issue they were reporting than did any of the politicians they were interviewing.

But why should that be surprising? Channel 4 has more resources to devote to policy than does any political party. Channel 4 spends 54 million pounds a year on news, documentary and current affairs programming. The two main parties each spend something like 10 million a year, but most of that is spent not on “content”, but on content distribution – posters, leaflets, etc.

British political parties’ policies are being constructed on an almost totally amateur basis, compared to the media – and I think it shows. There are think tanks, but I don’t think they turn over tens of millions a year.

(It must be noted that in the US they spend a lot more on politics, but don’t seem to get noticeably better policies.)

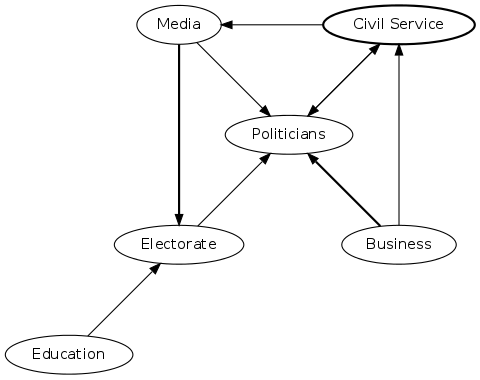

MPs get paid by the government, which is extra resource to the parties not counted in their budgets, and The civil service plays a role in developing policies for the ruling party, but MPs are paid to be MPs, not to develop policy, and the civil service has its own goals and constraints and is not under the control of the Labour party.

It seems that Channel 4’s 2007 policy on higher education was the product of more research and investment than went into the Labour party’s. It’s also relevant that political parties have an incentive to be vague about policy, whereas media organisations can afford to be more specific and clearer – they gain more by being provocative than by being right. This means that media are in a way more motivated to work out detailed policies than parties are

What does this mean?

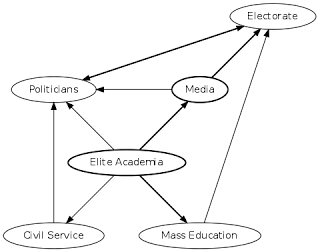

First, I should be less sceptical than I have been about the “power of the media”. I previously felt that, since the media is constrained to doing what gets it audience, its independent influence on policy is small. However, if what it needs to do is to provide some alternative policy with which to challenge politicians, but it has relative freedom to choose which alternative to develop, then its independent influence is greater than I had thought.

Next, why is it the case that we (as a society) invest more in reporting politics than we do in politics itself. Either something is seriously screwy, or we value politics as entertainment more than as a way of controlling government. Or both.

I think it’s quite clear that the population does treat politics mostly as entertainment. The resemblance between Question Time and Never Mind the Buzzcocks is too close to ignore. If someone arrived from another planet and had to work out which of the two concerns how the country is governed, I think they might find it tricky. (I think they get similar numbers of viewers). There are even hybrids like Have I Got News For You to make it more difficult still.

Further, I think voters are correct to see politics primarily as entertainment. Since my attempt to construct an argument that voting could have a non-negligible probability of affecting an election – the infamous correlation dodge – died a logical death, I am left with the usual reasons for voting – primarily how doing it makes me feel. Those reasons apply equally well to voting for Big Brother or Strictly Come Dancing.

Boris Johnson’s election as Mayor of London in 2008 is consistent with the theory that politics is a branch of the entertainment industry. Boris won because people liked him on TV, not because they had any confidence he’d do a good job. In fact, it simply doesn’t matter whether he does a good job or not.

Whatever the budget of the GLA, the actual amount of cash he can shift from one activity to another over the next four years is probably on the order of only a few millions. He can change a few buses, approve a few “don’t knife each other, there’s good chaps” posters, approve or deny one or two large buildings.

On the other hand, he will be on television a lot, and get a lot more attention, because now he’s (drum roll) In Government. And if you treat each of his appearances as a light entertainment programme, value it as equivalent to an equally entertaining non-political celebrity appearance, and multiply up the number of such appearances over the four years, his entertainment value to the voters easily outweighs whatever costs might be imposed on the voters if he is a Bad Mayor in a policy sense.

And in fact the predictable cost of Boris vs Ken is near enough zero. Who knows, Boris might even be better. While the predictable difference in entertainment value is huge – not only is Boris more entertaining than Ken on a level playing field, but more importantly the Ken show has run for eight years and we’ve seen all the best bits.

My point is that (a) Boris has been elected because he’s funny and people are bored of Ken, and (b) This is, with apologies to Bryan Caplan, rational voting.

And of course, it is nothing new: Ken was elected in 2000 for just the same good reason.

In conclusion, I think our system of government is one which selects leaders and policies as a byproduct of the entertainment industry. This might not be a bad thing: the traditional alternative is to select leaders and policies as a byproduct of the defense industry, which has its own problems.

Original three posts:

- December 13, 2007 News and Politics and Money

- December 15, 2007 Democracy and Entertainment

- May 4, 2008 Entertainment and Policy